Wheels of Change: What We Learned From Our Tour of Steel & Auto Sites in Detroit and Dearborn

Ariana Criste, Senior Communication Strategist

In the heart of Dearborn, Michigan, children's laughter at recess is drowned out by the industrial hum of nearby steel mills, power plants, and diesel trucks. For residents in Dearborn’s Southend, back-to-school means children playing on a playground in the shadow of nearby industry.

Above: the playground at Salinas Intermediate School with the Dearborn Industrial Generation power plant looming in the background.

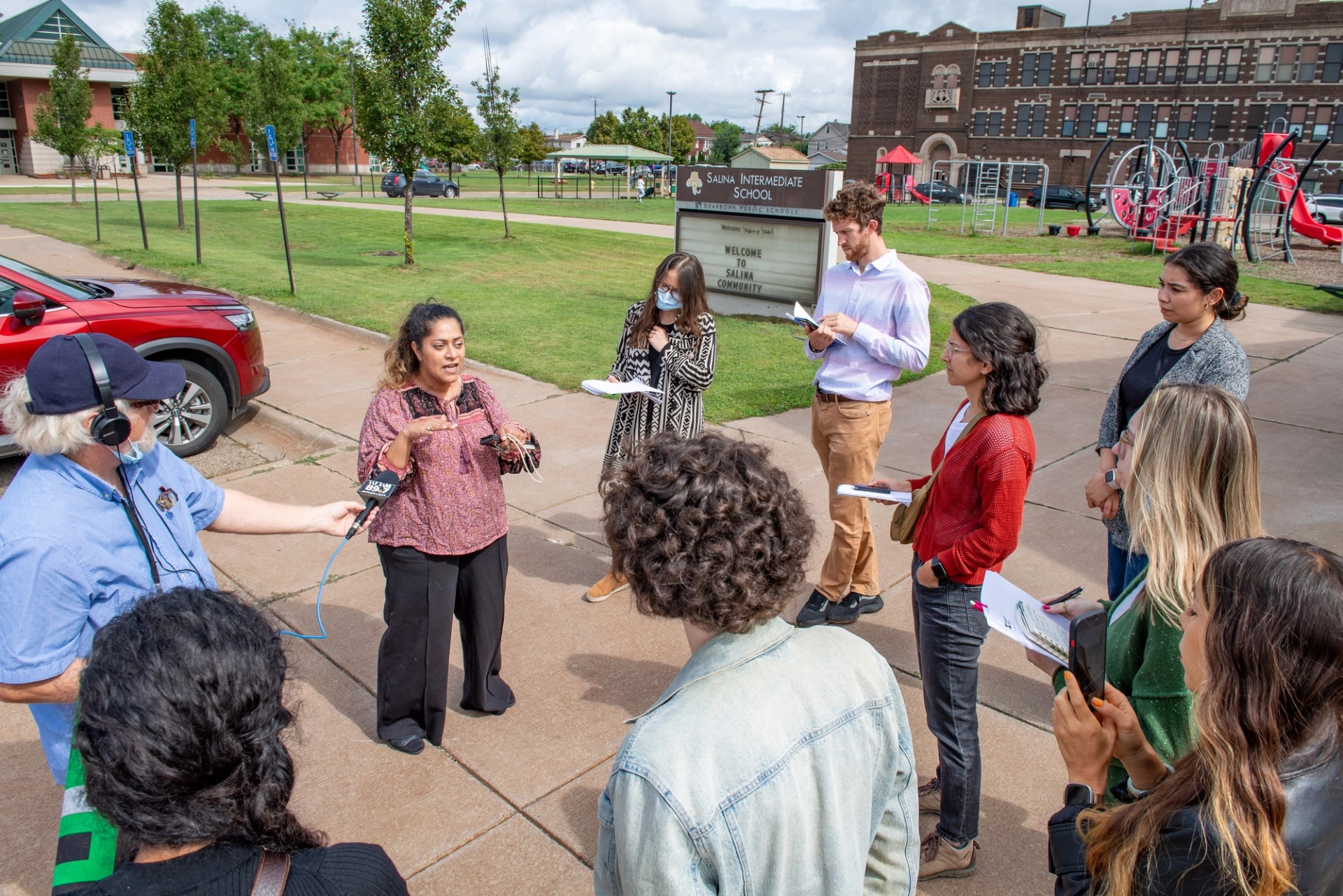

“Our kids play on a playground 150 feet away from a methane power plant and just across the street from a steel plant,” explained Samra’a Luqman, a resident and activist from Dearborn.

In the heart of this community lies a battle for clean air, healthy communities, and justice. Samra’a's words echo the concerns of countless families living in the shadow of industry giants.

“We live in a cancer cluster. My family and neighbors are impacted and dying. Within six months of birth, my son developed a tumor and had it removed. My mom is in remission. When COVID came to our area, it cleaned out our grandmothers, our grandfathers, and our parents. We were severely impacted because the steel industry refuses to clean up its mess,” said Luqman.

Above: Samra’a Luqman speaking to a crowd of reporters during the tour

Samra’a's story vividly illustrates the profound human and environmental toll inflicted by steel manufacturing, serving as a poignant reminder of the compelling need for transformative change within this industry. But how can we bring about this essential change?

In this blog, we will walk you through our recent tour of steel and auto manufacturing sites in Detroit and Dearborn in advance of the Detroit Auto Show. We will shed light on the environmental and health challenges faced by local residents as a consequence of steel and automaking and explore how to chart a path to a cleaner, more sustainable future for these industries.

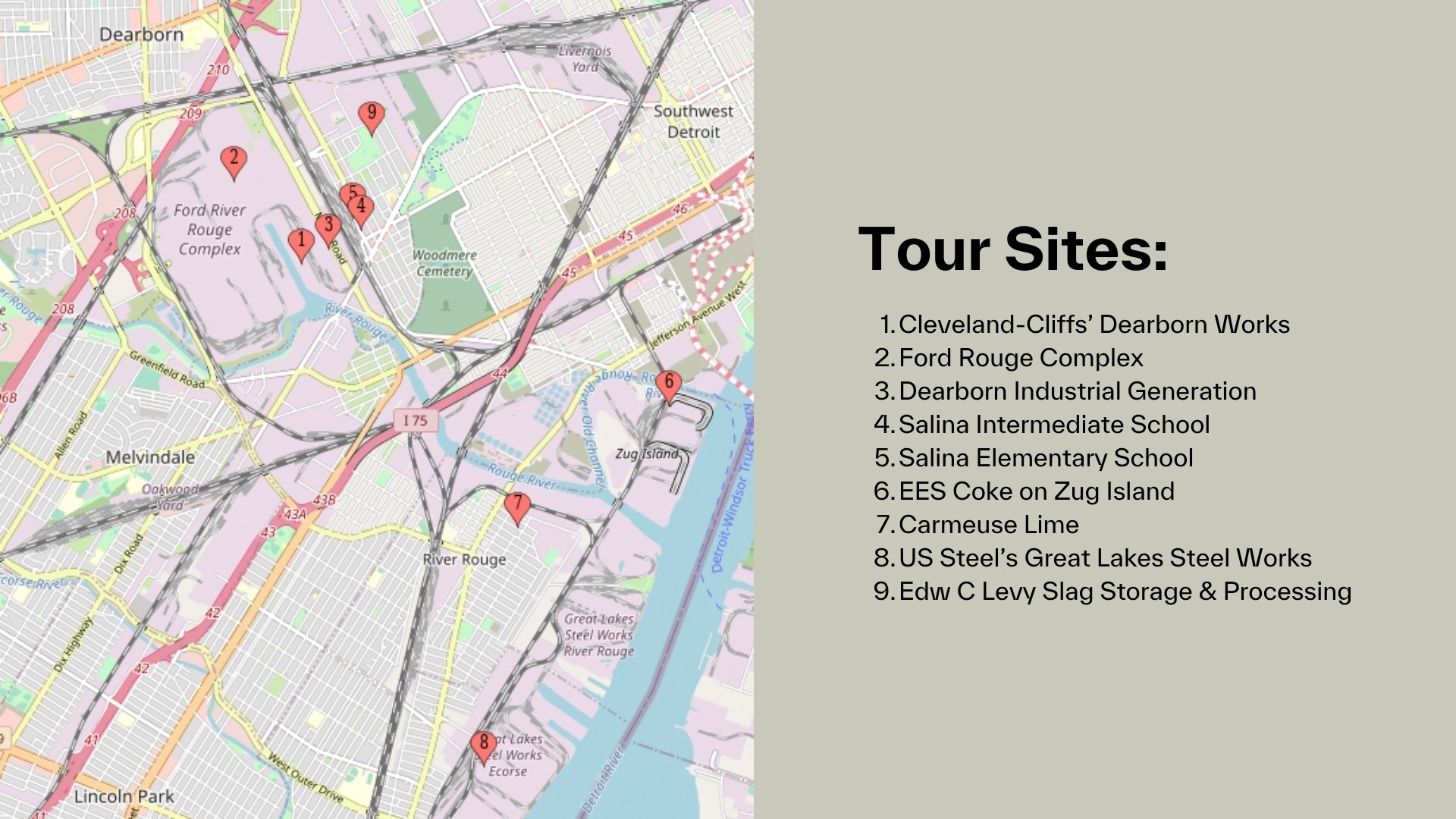

Above: a map of the sites explored on our tour

How Steel is Made

Today, almost 70% of climate pollution from the American steel industry comes from just eight steel plants, including Cleveland-Cliffs Dearborn works, all in the Great Lakes region. These facilities are owned by just two companies: U.S. Steel and Cleveland-Cliffs, which is currently bidding to buy U.S. Steel.

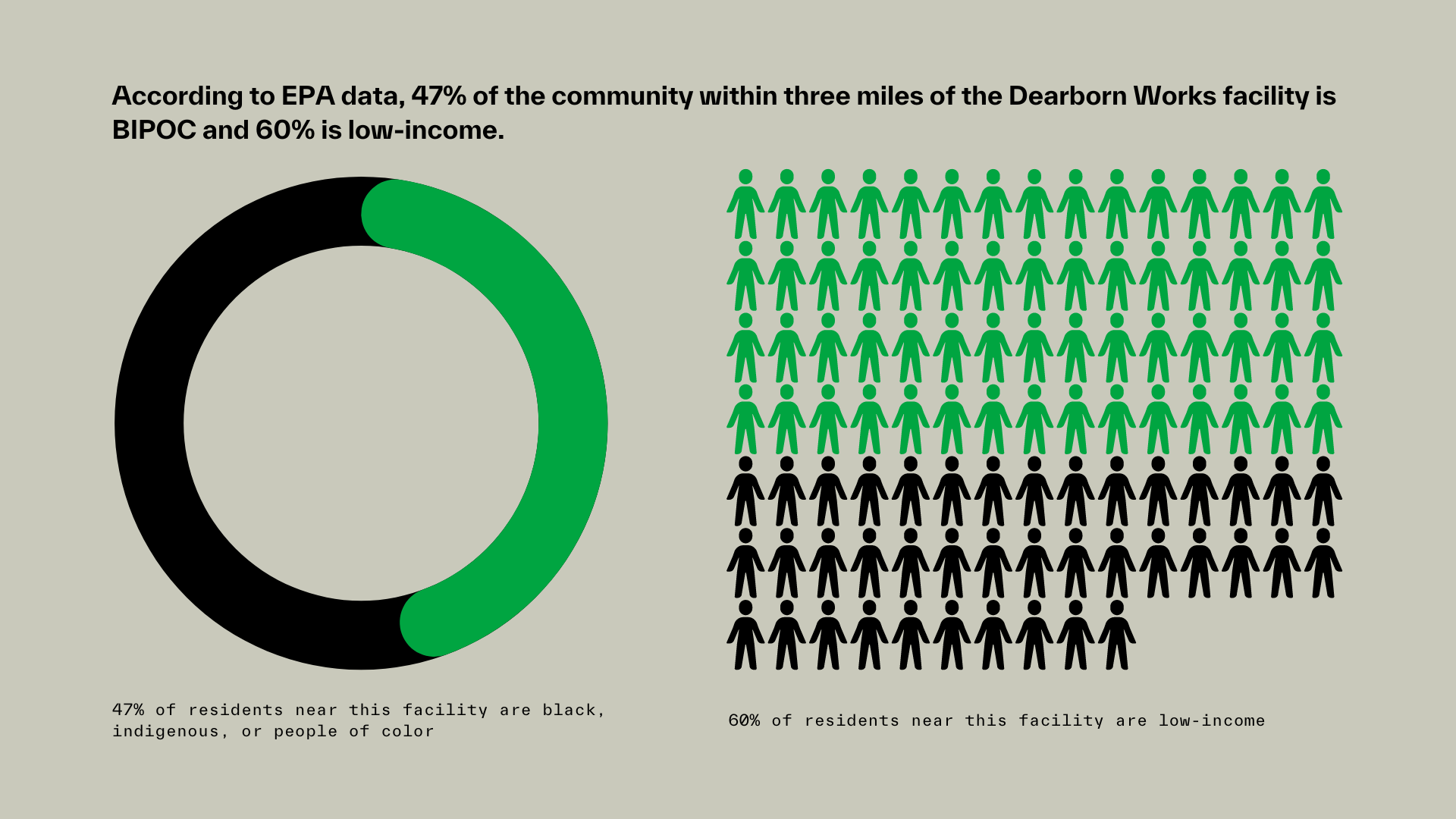

Most new steel is made by heating iron ore, coke (cooked coal), and lime in a giant furnace called a blast furnace. These blast furnaces emit toxic pollution, including heavy metals and particulate matter, disproportionately affecting Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) and low-income communities. According to EPA data, 47% of the community within three miles of the Dearborn Works facility is BIPOC and 60% is low-income.

Our tour highlighted the impacts of making coke and lime to feed into dirty, traditional steelmaking:

How coke-making at EES Coke impacts nearby communities

At EES Coke on Zug Island in Detroit, metallurgical coal is heated to produce coke for blast furnaces. This facility, which supplies coke to steelmakers, including Cleveland-Cliffs, ranks second in Michigan for sulfur dioxide and particulate matter pollution among industrial facilities (excluding power plants), according to Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) data. In addition to coking coal driving most carbon emissions from steelmaking, coke ovens are a significant source of health-harming pollution, responsible for more than 40% of carcinogens released during blast furnace steelmaking.

Theresa Landrum, a lifelong SW Detroit resident, retired autoworker, and activist, shared her family’s history with the plant on the tour, “My father worked on Zug Island and brought chemicals and dust from work on his uniform into our family home. My mother and father both passed from cancer, and my sister and I are both cancer survivors. You can connect the cancer rates in our community to the pollution from these industries.”

Theresa’s story highlights the inseparable connection between the well-being of workers at these facilities and the surrounding community's health, underscoring the critical importance of healthy jobs and a clean environment. “When we talk about pollution, we need to talk about the pollution inside and outside of these facilities that impacts workers and residents,” explained Landrum.

Above: Theresa Landrum speaking in Detroit’s Delray neighborhood with EES Coke on Zug Island in the background.

The cumulative impacts of heavy industry

Further along Detroit’s River Rouge is Carmeuse Lime, a facility that produces lime, another crucial component in traditional blast furnace steelmaking. While Carmeuse Lime's emissions may seem relatively minor compared to nearby facilities like Southwest Detroit’s Marathon Oil Refinery, it's important to think about the cumulative impacts of these facilities.

Despite Wayne County covering just 1% of Michigan's land area, it bears the highest concentration of industrial facilities monitored by the US EPA’s Risk-Screening Environmental Indicators (RSEI) in the entire state. The RSEI model analyzes industrial pollution, including specific chemicals, quantities released, and residents' proximity and exposure levels to that pollution.

According to the RSEI, Wayne County ranks as the highest-risk county in Michigan from potential health risks posed by pollution and is among the worst in the entire United States.

In everyday language, the health dangers tied to pollution and environmental issues in Wayne County are some of the most serious in Michigan and the U.S.

This underscores the impacts of cumulative exposure to industrial pollution on the health of Wayne County residents. Research has established a direct link between this combined exposure and severe health consequences, including COPD, asthma, respiratory infections, cardiac diseases, cancer, and premature death. A 2016 study revealed that cumulative air pollution exposure in Detroit alone leads to 721 premature deaths and 1,500 hospitalizations yearly.

As we grapple with these cumulative impacts, it is clear that urgent and comprehensive solutions are needed to safeguard the health and well-being of residents in communities like Detroit and Dearborn.

The intertwined nature of steel and automaking

The tour then stopped at the Ford Rouge Complex, an industrial park that houses Ford Motor Company’s largest factory and the Cleveland-Cliffs’ Dearborn Works integrated steel mill. Here, we saw how interconnected the steel and automotive industries are.

Automakers are key buyers of the steel made at facilities like Dearborn Works. In 2022, the automotive sector was responsible for approximately a third of Cleveland Cliffs' and U.S. Steel's domestic sales. As the industry shifts towards electric vehicles (EVs), pollution from the auto supply chain is coming into focus. A critical starting point is steel, which is approximately 65% of the current average vehicle weight and 20% of the embodied emissions of an EV, according to Mercedes-Benz.

Erika Thi Patterson, Auto Supply Chain Campaign Director at Public Citizen's Climate Program, emphasized the importance of automakers as key customers to the steel industry, “If automakers committed to procuring decarbonized steel, that would send a powerful signal to steel producers to invest in the transition.”

“Automakers need to leverage the industry’s purchasing power to cut emissions in local communities, eliminate human rights abuses throughout their supply chains, and propel a just transition for steelworkers in the US - into cleaner, union jobs making green steel,” explained Thi Patterson.

Above: Erika Thi Patterson speaking to tour attendees on the tour bus

Although Ford and GM have signed the First Movers pledge to purchase 10% near-zero emission primary steel by 2030, no US-based automaker has signed a green steel contract.

On the tour, Dearborn resident Samra’a Luqman posed a question to automakers like Ford, “Do you value human lives enough not only to commit to electric vehicles but also to ensure that these electric vehicles are produced through a green steelmaking process?”

Reline or Reimagine: The Crucial Decision Facing Dearborn Works and the Steel Industry

The U.S. steel industry stands at a critical juncture: it can either extend its reliance on fossil fuels, perpetuating environmental and health issues in steel communities, or take a bold step toward reimagining the industry for a cleaner, more sustainable future. One of the most pivotal decisions in charting this course towards sustainability is whether companies opt to reline existing blast furnaces.

Blast furnaces require a major maintenance project where the bricks lining the furnace are replaced, known as a reline, approximately every 18 years to continue to operate efficiently. In 2007, the blast furnace at the Dearborn Works facility was torn down and rebuilt, indicating that the furnace would soon need to be relined. According to estimates from Industrious Labs, relining Dearborn Works would cost approximately $275 million and extend the plant’s life by almost two decades.

Cliffs has not announced plans to reline its Dearborn Works blast furnace, but advocates are concerned that this announcement will soon come. Relining extends a coal-burning steel plant's life by an estimated 18 years, pushing the sector further away from the trajectory required to decarbonize. This is a stark reminder of the need to transform the industry to prevent additional harm to human health and the climate.

By not transitioning, the industry will surrender the green steel market to other countries, with tangible consequences for American workers and communities. The tour started at U.S. Steel’s Great Lakes Steel, which permanently idled its blast furnace and basic oxygen furnaces in 2020. This move resulted in an estimated 1,000 workers losing their jobs. On the other hand, recent reports, such as one by the Ohio River Valley Institute, have shown that a transition to green steelmaking could grow the total number of jobs supported by the steel industry. Instead of doubling down on dirty blast furnace steel, steelmakers must use this opportunity to invest in clean alternatives.

Above: Activists pose in front of the blast furnace at the Cleveland-Cliffs Dearborn Works mill

Opportunities for transformation

Now is the time to explore transforming facilities like Dearborn Works into pillars of a green economy, providing good jobs and cleaner air for workers and communities. The good news is that the potential for fossil-free steel production is a reality today, thanks to a proven method of ironmaking known as direct reduced iron (DRI), which can be powered by green hydrogen generated from renewable energy. While facilities adopting this technology are already under construction worldwide, there are currently no announced plans to build fossil-free steel plants in the US.

As Industrious Labs Steel Director, Hilary Lewis, explained on the tour, “There is a big opportunity for Michigan to be a leader in clean manufacturing, and now is the time to start.” The $200 million Onshoring Clean Energy Supply Chain Tax Credit that Governor Whitmer has proposed could be leveraged to modernize this facility, in addition to the $6.3 billion set aside for industrial decarbonization in the Inflation Reduction Act and Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill.

If US steelmakers seize this moment, they can become leaders in green steel, creating jobs and reducing harmful pollution while meeting the growing demand from the auto industry.